Last year, we hosted four incredible interviews with folks driving radical collaborations across the globe. Our world has transformed so much in the time since, but the wisdom of these great leaders sustains. Take a listen.

We are actively engaged in the dialogue and debates of our space: on issues of social justice, global development, and democratic innovation, and on the ethics and methodological evolution of design, mediation, and co-creation practice. More of our writing can be found at Medium.

We are thrilled to welcome Emily Herrick and Shruti Sannon to our growing team! Emily will join us as Design Intern. A swiss-army knife of creative talent, Emily previously designed book interiors at Penguin Group and has experience spanning web, print, and packaging design. Shruti comes to Reboot as Programs Intern. She brings experience in marketing, strategic communications, and psychology, and her previous areas of research include Goth kids in Singapore and middle class housewives in New Delhi.

Our ever-growing access to information and tools has profoundly changed the way we can use, digest, display, and share data. Put an internet connection and a laptop together and you have a tool that can empower people—regardless of experience—to visualize and dictate data’s meaning and impact.

But as data use becomes more frequent, more creative, more far reaching, is the information we share and the way we share it using data accurately? Are we sharing knowledge responsibly or perpetuating the obscurity of data?

In a recent post, “Can Data Visualizations Help Mediate Between the Worlds of Research, Policy, and Practice?” AidData addressed data visualization—a way to visually represent raw and unprocessed information in a clear, sharable, and relatable way. The abundance of data we have access to is certainly overwhelming and, as the post suggests, a “vortex”. Data visualization offers hope for a shift from a whirling mass to something more real. The above post stressed the need to convey “relatable information at a glance,” highlighting single layers within complex data as a means of reaching audiences previously naïve to the information presented.

But while compelling and accessible, data visualization often falls prey to the very data misrepresentation that it seeks to avoid. The intention of reaching and being relatable to many people is noble, but delivery often seems to perpetuate rather than tame the swirling vortex.

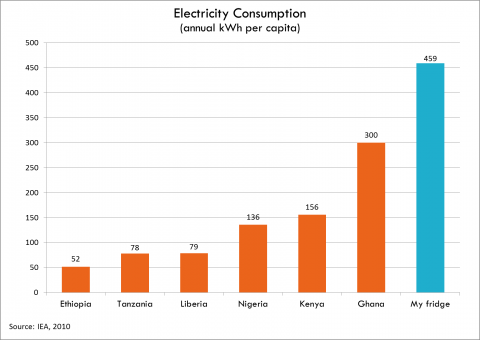

Take for example the ideal set in the above AidData article. At first glance, we can see that “My Fridge” consumes more electricity per capita than Ethiopia, Tanzania, Liberia, Nigeria, Kenya, or Ghana. We’re led to the shocking conclusion that our visualization creator’s fridge is more advanced than these African nations.

But what is this visualization not telling us? Why do these nations consume low levels of electricity? Is it a reflection of electricity use or access? How does information compare to previous years? What are we supposed to do with this information? To its credit, the graphic has the ability to speak to fridge owners. But its purpose is hazy.

If the purpose of data visualization is to join previously separate worlds, it needs to go a few steps further; from being merely shocking to accurately compelling. It needs to build deep understanding through the creation of something that is both relatable and substantive. Visualization offers a lens through which we can view information, but that lens shouldn’t overlook context, causation, or other contributing factors behind the data.

This becomes especially important as data becomes readily available through open data initiatives and technology innovations. Data visualizations have the power to inform policy, service design, and our collective thinking. Shallow messages won’t cut it—real people and real lives are often found at the roots of data; they are a crucial component of the context we need to encourage understanding of citizens affected by policies and programs. People are the substance behind the data, and policymakers need to make decisions based on people, not numbers, to design inclusive policies and services.

For example, in a recent attempt to visualize data on public spending, we started with data on cost increases for public service projects. It quickly became clear that visualizations headlining 200% cost increases would create impact at first glance, but misrepresent the story behind the numbers. There are costs that simply weren’t budgeted for, and there are also costs that are necessary to deliver the best possible outcome.

It became clear that we had to show a greater depth of information to get from a data-driven narrative—“This project cost 200% more than it was supposed to. It was a budgeting failure.”—to a narrative embedded in context—“The project cost 200% more than was budgeted for, but its scope (road length) doubled and included additional actors and aspects (road materials, walkways, streetlights, drainage) not accounted for at the outset.”

Data consumed through visualizations “at a glance” runs the risk of discouraging engagement and understanding of the people the data is trying to represent. That said, we’re also up against the daily challenge of keeping up with short attention spans in our fast-paced digital world—anything that doesn’t immediately connect to the viewer is likely to be overlooked, losing the battle to Twitter in a neighboring browser tab.

But we can’t overlook the fact that the causation or insights behind related data simply don’t get the consideration they deserve in a graph with a five-second lifetime. And as designers it’s our responsibility to visualize data in a way that embraces the inherent complexity behind numbers.

As Victor Papanek once wrote, “Design has become the most powerful tool with which man shapes his tools and environments (and, by extension, society and himself)…This demands high social and moral responsibility from the designer. It also demands greater understanding of the people by those who practice design and more insight into the design process by the public.”

Let’s look beyond the seduction of graphs seeking a shock factor, beyond quick one-glance charts. According to John Emerson, “People who might not be persuaded by raw numbers or statistics may be more likely to understand and believe what they see in a chart or graphic.” It’s our job to facilitate, not manipulate, their understanding.

Last week, we explored how policymakers can channel empathy in policymaking, using as an example our work with UNICEF to identify the diverse needs and challenges of children in Nicaragua’s North Atlantic Autonomous Region (RAAN). Our community-based approach highlighted success stories of people designing programs to fit their own needs. Today we’ll go to Puerto Cabezas, RAAN’s capital, to see how local programming has stepped in to provide unique opportunities for the region’s children.

School is out for the afternoon, and boys across Puerto Cabezas are drawn to the ball fields. Some biking and others even running, they are rushing to get to practice on time.

These are the boys of the Puerto Cabezas Baseball Academy.

Dr. Wilfredo Cunningham Kain first funded the Academy to encourage his young son’s love of baseball. Over the years, the Academy has evolved into an after-school and weekend program that supports more than 400 boys on the road to manhood.

Some dream of growing up to play in the U.S., while others play for pure love of the game. For many, baseball provides a much-needed diversion in a place with few extracurricular opportunities for youth.

A program like this is greatly needed in Puerto Cabezas. Young people often receive little support at home and see few options for their futures. They lose interest in school and, in a place lacking healthy, organized activities, many boys turn to gangs, drugs, and alcohol for solace.

There are few systems to catch these boys as they begin to withdraw.

The Academy serves as both a safety net and a springboard. Each coach assumes a somewhat overburdened mentor role overseeing about 100 boys. The program funds all expenses to prioritize inclusivity regardless of financial background.

And there are rules: the boys have to arrive on time with clean uniforms. They have to keep up their studies by going to class. And they have to get at least one adult family member involved in the program.

This last requirement is the least followed. It’s hard—not a lot of kids have parents who can spend the time. But baseball is a great forum to build relationships. Dads find a sense of pride watching their sons slide into home or throw a winning pitch.

The program actively seeks to place players in the Nicaraguan national team and minor league teams abroad. Although the program is only six years old, its team of 11-13 year-olds has held the national youth championship for the past five years—a national record.

But Dr. Cunningham Kain isn’t shooting to field the country’s next all-star team. He has greater plans. He envisions a formal baseball academy that produces not just players with top skills but, more importantly, young men with strong values.

The academy is the ideal place to teach discipline and values that stick. These values are tied to an activity the kids truly care about, fostering personal investment in baseball and studies. It matters to the kids if they have to do their warm-up run alone because they’ve arrived late. It matters if they can’t play because they haven’t been going to class.

While the program has not been formally evaluated, its growth, and the players’ dedication to keeping up their end of the bargain, speaks for itself.

Dr. Cunningham Kain tells the success story of a boy who had been withdrawing from school. He was getting heavily involved with gangs. He seemed to be out of control, beyond help. But this boy started participating in the program and discovered an innate talent for the game. Over time, and with the support of coaches and teammates, his confidence and self-esteem grew. He re-engaged in school, dedicated himself to practice, and eventually became the program’s star pitcher, playing at the national level.

The Academy’s programming is inherently adaptive, changing to fit needs and make the most of available resources. Driven by passion for its mission, this organic growth has been one of the program’s strongest attributes. The program has not succumbed to over-regulation, which would curtail the flexibility that has enabled it to support children through difficult family situations, trouble with gangs, and other obstacles.

Dr. Cunningham Kain contributes personal funds to the program, but he is actively seeking external funding to expand the program and hire a team social worker, a child psychologist, and more coaches trained in nurturing boys’ athleticism and character.

There is significant potential to increase the program’s impact, but until it receives more funding, it will continue to run largely on heart.

Above photo: The Puerto Cabezas Baseball Academy is a homegrown program that teaches responsibility and social values while giving boys the opportunity to play the game they love.

Panthea will address masters students in the Design for Social Innovation Program‘s guest lecture series at the School of Visual Arts on February 6. Students will have the opportunity to learn about Reboot’s work and engage with Panthea on a variety of subjects related to our programs.

In Nicaragua’s Northern Atlantic Autonomous Region (RAAN), there is no single experience of childhood.

For a child in seaside Prinzapolka, a highlight of daily life might be playing on the town’s sandy beaches. In rural northern Wangky Maya, the picture of home might be mother and sisters standing over a smoking wood stove in the yard. Children may spend their after-school hours helping split firewood and carry well water home; others might join friends around the neighborhood church for a pick-up soccer game or help with a small bread baking business run out of the family house.

Equally diverse are the constraints affecting these children’s lives: economic weakness in RAAN, poor physical infrastructure, lingering effects of conflict and natural disaster, and sociocultural complexity. Almost one-third of RAAN children suffer from chronic malnutrition and poverty affects 34 percent of children up to 17 years of age—nearly twice the rate of poverty in and around Nicaragua’s capital, Managua.

For policymakers in RAAN keen to draft a comprehensive policy to protect children’s rights, this reality presents a challenge: how to design a policy that can account for the diverse array of circumstances and needs facing the children of the region?

Empathy is a good place to start.

Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of others. Channeling empathy into the policymaking process means intentionally seeking a deep understanding of the lived experiences of those a policy will affect to inform how that policy is designed.

Previously, we’ve written about how operationalizing empathy in international aid institutions can support more successful development programs. When applied to the policymaking process, an empathetic approach helps ensure: 1) the process is collaborative, grounded in regular engagement between policymakers and constituents; and, ultimately, 2) the resulting policy is both inclusive and appropriately tailored to the local context, able to serve as an effective framework for guiding programmatic interventions.

Together with UNICEF, we implemented this approach to help channel empathy into the policymaking process in RAAN. Some of the concrete steps we took included:

Our work in RAAN was a first step toward an approach to policymaking that channels user research and individual empathy into contextualized policy interventions backed by political investment. But the process illuminated key challenges that will require further exploration to develop this approach.

First, how can an empathy-based policymaking approach be made more accessible and less overwhelming? This approach can be time- and effort-intensive.

Partnerships have the potential to ease the burden, but significant iteration will be required to determine the sweet spot for cooperation and stakeholder involvement depending on the environment and political interests.

Second, how can the results of empathy-building user research be channeled into sound policy?

There is no “off-the-shelf” formula to pull from here. Policymaking is, ultimately, a political activity and greater empathy is not necessarily a guarantee for more politically palatable solutions. In RAAN, this approach cultivated a shared experience for institutional factions with contentious histories, allowing them to work productively together. But this might not have been the case in another context.

With this in mind, the challenge is now to further explore the strong potential of greater empathy in policymaking to help manage and channel political interests in regions worldwide, while serving those whose needs are being overlooked. If we are able to continue working toward a more sophisticated approach to policymaking in different contexts, we will succeed in truly valuing those for whom these policies are built.

Above Photo: A RAAN policymaker builds the story of community member archetype the research group created. Archetypes helped to put a human face on research findings during Reboot’s recent work in Nicaragua.

The word “politics” is loaded. It conjures images of backroom deals, self-interested maneuvering, and elite manipulation. It carries a negative connotation in any context. Outside interference in political affairs is even worse: as unseemly as politics can be, it’s meant to stay within the family.

Nonetheless, there’s been an increasing discussion about politics in aid over the past year.

With aid-receiving countries pushing back on interference by donor nations, technocratic multilaterals frustrated by stymied reforms, and academics searching for the root causes of institutional failures, the political factors that both influence and result from aid have become more apparent.

It’s long been an open secret that bilateral agencies use aid to support friendly regimes. And the sector is admitting that aid has political impacts—both intentional and unintentional—within receiving countries. Though the historical and economic relationships between many aid-giving and aid-receiving countries makes this a sensitive issue, the pretense that aid should be separate from politics is crumbling in the face of the facts.

Even this is not enough. We need to go one step farther: not only is aid political, but aid also needs to be politically intelligent. Political economy analysis, though increasingly popular in the sector, only gets us halfway there. We need to get straight to political analysis.

By understanding what we mean when we say that aid is political, the path to politically intelligent aid becomes clearer.

Of course. But this question actually misses the point somewhat.

When money is transferred, there are economic impacts. When governments interact, there are political impacts. That has more to do with the definition of “politics” and “economics” than it does with the nature of aid.

The political realm is much broader than the power struggles around elections or policy decisions. Politics are how the affairs of any group of people are managed. People in any context will debate, negotiate, advocate, collaborate, and conflict over how to use their collective resources or power to pursue better lives—and even over defining what “better lives” means.

Each context’s politics are shaped by the institutions that have been established, cultural norms, and the incentives and accountabilities that various actors face. Whether in a legislature or a ministry, a university department or a corporation, politics exists in all arenas.

In the case of aid, money flowing from one country to another—whether through official public channels or through private actors—influences the contextual factors in the receiving country. Money changes the incentives faced by countless actors; technical assistance changes professional cultures and institutions; contracts change accountabilities. A seemingly simple service delivery program can shift local politics by serving one constituency more than another. National-level programs with significant resources have even more impact, as they can become focal points for power struggles.

Oxfam’s Duncan Green recently used the term of “political sterilization” to describe potential channels for aid to have benefits without disrupting politics. I’m doubtful that such channels are possible. Worse, I’m worried that the very real effect of fooling ourselves into thinking that aid can be apolitical—which happens in social service and cash transfer programs—is that we fall victim to someone else’s political priorities. Even no aid at all is a political choice.

New political thinking in aid is driven by the frustration felt by the economists and technocrats who have long steered aid thinking: the technical analysis is sound, yet these darn politics keep getting in the way. As the “Washington Consensus” economic policies failed in the face of institutional capacity constraints and political blowback, aid institutions broadened their view to include governance and politics. The political scientists were offered a seat at the table.

This has meant a rise in political economy analysis, as described in a recent World Bank report. Aid agencies are increasingly using these methods to better understand the political landscapes, including the interest groups and incentives that determine who will benefit from, support, or oppose particular engagements.

Unfortunately, there’s a big difference between “politics” and “political economy”. The lobbying firms and advocacy groups on K Street in DC don’t conduct political economy analysis. The underlying socioeconomic, cultural, and historical dynamics are important shapers of political contests and we do need to think systemically. But politics is ultimately about people. Political economy analysis, in contrast, intentionally avoids focusing on individual actors.

In order for aid agencies to be more politically effective, they need to understand the people involved. Their analysis has to go beyond the broad structures to the particular coalitions and individuals making decisions. At a recent event hosted by the Center for Global Development, Pablo Yanguas noted that this already happens in most aid agencies, but it’s a bit under the radar and not very systematic. Staff are navigating the contexts they face, with informal or implicit political analysis guiding their decisions.

This analysis could be strengthened if it were a program requirement (“mainstreamed”, as they say) or if political savviness was considered a management competency (though admittedly, a difficult one to evaluate in potential staff). Most importantly, it has to happen on a tighter loop than a pre-program political economy analysis. It has to be iterative throughout the course of engagement, synthesizing evidence from multiple sources, informing action steps, and willing to make calls in the face of ambiguity with less than academic levels of rigor.

That aid has political impacts is obvious. It’s high time we found ways to understand what those are, and ensure that they are more positive than negative. Making aid practices more politically intelligent will be one step in that direction.

Above Photo: Nigerians in Nasarawa talk about a donor program in their state.

The Aspen Institute has launched Panthea‘s open gov series as an official 2013 FOCAS report hosted on a new, dedicated website. The report highlights key elements of equitable and accountable governance to motivate dialogue around open governmen

Panthea Lee shared lessons from our recent projects, discussed Reboot’s past and future growth, and engaged in lively Q&A with students at the School of Visual Arts this afternoon.

For years corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives have been applauded, criticized, and debated. Between headlines like “When Corporations Fail at Doing Good” and “Is Responsible Capitalism a Farce?”, one insight has become abundantly clear: CSR initiatives are often a necessary part of business, but those with the potential to make a difference are easier discussed than delivered.

This is especially true for companies supporting social services in complex environments that are new to them. On the one hand, companies have a great deal to offer the social sector: financial resources, human resources, managerial experience, technical expertise. And, for most companies, there is little choice—consumers, employees, investors, and even governments are all demanding CSR initiatives.

But when companies enter the social sector, there are many challenges to overcome. Many companies are most interested in numbers and marketing, showing little effort to discover added value—social or environmental benefits—beyond profits. Even when companies have genuine intentions, they may invest millions of dollars in CSR initiatives but take on a role that may not be appropriate for the project’s local context. Many companies are simply unaccustomed to contributing to and measuring the success of social service projects.

The reality is that the social sector is not a private company playing field. In the design of an effective CSR program, the donor and implementer need to identify an appropriate way to apply corporate skills to on-the-ground realities. This is especially true of companies whose products and expertise, if properly channeled through a CSR initiative, can make discernable improvements to public health in some of the poorest communities.

So what makes some initiatives more effective than others, and what factors should be considered in the design of CSR programs?

Corporate-NGO partnerships allow donors and implementers to fill knowledge, access, or expertise gaps; be it knowledge of local landscapes, access to funds, or relationships with local institutions. But the unique skill sets and mandates of NGOs and corporations are married to the organizational structures those skills have demanded. With such different backgrounds and expertise, companies and NGOs face the daunting task of understanding each other’s widely different operating contexts and program expectations, and learning how to make them function together.

NGOs and companies are in need of work practices and mechanisms that facilitate deeper understanding of each other’s needs and the needs of those served. Empathy can help ground these practices—and related interactions—in a more nuanced understanding of the perspectives, contexts, constraints, and histories that inform each side’s organizational structures, operations, and communications.

The process of integrating empathy into projects can be described as operationalizing empathy. Operationalizing empathy in partnerships between NGOs and corporations has the potential to ensure effective application of company resources in social service projects.

To operationalize empathy effectively, NGOs and companies would do well to remember that partnerships do not exist in a vacuum. Corporate donors should be aware that they are likely one of multiple public and private donors that an NGO is working with simultaneously and learn to tailor demands to the NGO’s available resources. Microsoft, for example, fully expects to be one of many donors on a given project, deliberately ensuring the NGO takes the lead in drawing support from other funders. Similarly, implementing NGOs need to be aware that many CSR projects hold a secondary citizen status within companies; those in charge are often forced to defend the value of a given initiative—far from an easy task in the business world.

Marks & Spencer and Oxfam have achieved a partnership that is often upheld as an example of collaboration based on knowledge sharing and mutual, defined goals in their clothes recycling campaigns. The partnership is well-aligned with Marks & Spencer’s business objectives and supported by strong communications campaigns. But mission-aligned pairings like this are still exceptions.

Those working in the space of corporate-NGO partnerships recognize a need to deepen understanding between partners. Groups like the mHealth Alliance have found success fostering understanding among organizations from private, public, and NGO spaces. Through working groups, summits, and knowledge sharing, organizations can identify areas where their perspectives align—a base of collaborative action. CiYuan Corporate-NGO Partnership Development also facilitates cross-sector collaboration through roundtables and consultancy services to enhance philanthropic endeavors in China.

These are strong starts, but in order to ensure successful partnerships we need to go one step further. We need to explore the context and motivations behind NGO and corporate behaviors and identify where these motivations align.

Achieving collaborative outcomes remains difficult, because what you see depends on your vantage point. And few vantage points are as far apart as those of a massive conglomerate and a 10-person NGO. But by beginning to understand and contextualize each side, we can begin to make funder and implementer vantage points mutually accessible to build foundations for long-term, effective partnerships.

Faaria’s coverage and critique of FAILFaire “Fail to Scale” was featured in UNICEF’s Stories of Innovation. Responding to efforts to embrace failure for future learning and growth, Faaria asks how these learnings can better lead us to target the heart of many failures: the unresponsive systems within which programs are implemented.

This is the sixth and final installment of an Aspen Institute Communications and Society program series on equitable and accountable governance shared over a six-week period. The series draws on conversations from the 2013 Forum on Communications and Society to encourage constructive dialogue around open government.

Despite the great many initiatives taking root worldwide, the open government movement has yet to achieve its potential. Open data has been used toward civic ends for nearly a decade, yet its current focus appears disproportionately targeted towards improving the quotidian details of our lived experience. I’ll be the first to applaud the streamlining of public services, but a more efficient e-government is not the same as a more accountable open government.

In other words, enough with the gateway drugs. Let’s get to the hard stuff.

Let’s employ open government initiatives in service of scrutinizing special interests that undermine democracy. Let’s bring open government to bear on how campaign finance and electoral systems are considered by government. Let’s close the gap between what could be done in open government and what is being done.

To realize open government’s full potential, scale of adoption is required from both governments and citizens. To achieve scale of adoption, both sides require greater understanding of the full potential of open government.

It’s a classic chicken-and-egg challenge.

FOCAS 2013 participants agreed that establishing larger awareness of open government’s benefits among both government and citizens is a critical next step.

“Government officials need more success stories,” said Kathy Conrad of the US General Services Administration. “Before they invest, they want more proof beyond the same examples they hear all the time.”

Still, given the relative youth of open government, many initiatives struggle to demonstrate the kind of cost-benefit that public agencies or international donors seek. According to Tiago Peixoto of the World Bank, “[Public sector] funders may think a certain open government initiative shows promise, but they need to first understand the return-on-investment.”

Here, civic entrepreneurs have a role to play. “There are many conversations in government about what’s possible [in open government], and prototypes can help crystallize those opportunities,” said Nick Sinai of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. “That’s where outside partners can add value.”

Ellen Miller of the Sunlight Foundation agreed. She stressed the value of civic entrepreneurs who, compared to government, are more nimble and have greater freedom to experiment—critical factors in creative problem solving. “In the early days [of open government], we didn’t fully recognize the importance of entrepreneurs to advancing open government. Today, it’s clear. The depth of [civic entrepreneurship] will be the source of innovation.”

But mission-driven entrepreneurs often have a tough time attracting funding, given private investors’ limited understanding of the open government space.

“Venture capitalists and others that fund small companies need to be educated about the potential of open data,” said Caitria O’Neill of Recovers.org. “They want proprietary data, and the concept of open data is anathema to them.”

For open government to move forward, perceptions need to change.

The work of the Open Data Institute (ODI) may prove instructive. ODI is a UK-based non-profit that seeks to engage diverse communities in catalyzing open data culture.

“Part of our work is changing perceptions of what open data is and what it can do,” said ODI’s Gavin Starks at FOCAS. “We want to show how data can help solve problems—it doesn’t matter the sector. We need global momentum from global stories that drive awareness about open data and push for standards.”

ODI’s initiatives are diverse in focus and take many forms. It established a physical hub to give London’s open data community a gathering place. It curates resources to share knowledge about what works—and what doesn’t—when publishing and consuming open data. It commissions open data-driven artwork. And it seeks to encourage shared standards and professionalize practitioners through certification.

To demonstrate open data’s value to a wider audience, ODI’s Open Corporates illustrated the complexity, and potentially dubious practices, of well-known multinationals. It showed, for example, that Goldman Sachs consists of over 4,000 corporate entities globally, some of which are 10 layers removed from its US headquarters. Of those entities, approximately one-third are registered in tax havens. The campaign generated popular interest, including media coverage from Wired, the London Evening Standard and BoingBoing. As ODI’s Sir Nigel Shadboldt explained, to capture popular interest, we first need relatable narratives.

“From early on, we believed that demonstrating economic value was going to be important for the open data movement. This, in turn, would help drive social and environmental value,” said Shaboldt at FOCAS. “For open data to gain traction in the mainstream, we needed compelling stories to increase depth of impact and capture people’s imaginations to envision change.”

So far, ODI’s model seems to be working: 25 countries are seeking to establish their own national chapter, as part of ODI’s vision of a Global Open Network.

FOCAS participants saw the benefits of a US chapter of ODI to promote open data culture among key audiences, including the public sector; support professionalization of the field; and encourage dialogue and coordination between diverse actors.

Much like how Red Hat became the ‘missing’ salespeople for open source software, ODI USA would help prime and educate the market. Activities to help advance open government may include working closely with government officials to understand their current challenges, then to design and implement initiatives that help address them using open government principles or tools. Or helping journalists understand the potential of open data for public benefit and sharing these stories with their readers. Or educating funders about what open data is and what it can do to enable informed, strategic investments.

At FOCAS, several participants, led by open government technologist Waldo Jaquith, signed on to lead the development of ODI USA. They have already begun mapping their plans, answer questions such as: What can be adapted from the UK model and what needs to be different? Where would the US chapter’s efforts be most effectively allocated? What impact can it have on open government in America?

As the open government community works to educate diverse audiences on the potential of inclusive, transparent government, we must also ensure that not only are we preaching accountability, but we are practicing it, too. Since its inception, many have questioned the viability and utility of open government. For all the tools, commitments, and initiatives, how do we ensure they actually achieve their intended impact?

In 2001, political scientist Archon Fung and sociologist Erik Olin Wright questioned the sustainability of participatory governance models. Empowered, deliberative governance is an innovative approach, they believed, but is yet historically unproven. And based on their survey of initiatives at the time, they warned of unintended consequences: “[O]ne might expect that practical demands on [public] institutions might press participants eventually to abandon time-consuming deliberative decision making in favor of oligarchic or technocratic forms. […] After participants have plucked the ‘low-hanging fruit,’ these forms might again ossify into the very bureaucracies that they sought to replace. Or, ordinary citizens may find the reality of participation increasingly burdensome and less rewarding than they had imagined, and engagement may consequently dim from exhaustion and disillusionment.”

In 2007, civic technologist Guglielmo Celata, in reflecting on his Italian e-democracy site Openpolis, noted, “Administrators are interested in e-participation projects, but they want to reduce the possibility of issues emerging directly from citizens, and of course they try to change the nature of the project from a participative one, into a consultative one. A kind of Poll 2.0, if one wants to be cynical.”

From 2007 to 2013, a study from Spain showed that in many participatory governance initiatives, municipal governments simply cherrypick citizen proposals that reinforce the existing positions of political parties, special interest groups, or vetted experts. Other studies have reached similar conclusions: Initiatives are often designed to prevent citizens from freely providing input, only allowing them to choose from proposals already deemed agreeable.

And, in 2013, early reflections on Liberia’s Open Budget Initiative—one of its Open Government Partnership commitments—were not particularly encouraging. Under the Initiative, the Ministry of Finance had set up an electronic billboard outside its office in Monrovia as a bold symbol of openness. Yet several key aspects of the country’s budgets, including government compensation, remain in closed cabinets.

Of course, in discussing open government, we must steer clear of employing false binaries: A government is open or closed. A program is a success or a failure. But we should remember that the way an initiative is designed can help or hinder citizens’ ability to input on the processes of governance, a state’s ability to meaningfully respond, and our collective ability to ensure the initiative’s accountability. If we are to realize the potential of open government, we must be sensitive to these realities.

So as we continue to secure commitments, build tools, and launch programs, let us make sure we hold ourselves accountable for their impact on human livelihoods.

Yes, the open government community is still experimenting. But we must be thoughtful and intentional in our experimentation. We should first clearly define our goals and assess our progress towards them so that, as a movement, we can understand how to build upon our successes and learn from our failures. We should be honest in recognizing our biases to enable our own accountability to those we seek to serve. We should be sensitive to the needs of citizens and governments alike, and design solutions that meet the needs of both and don’t place unreasonable demands on either. And, as noted in this post, we need more widespread understanding of the benefits of open government before we can realize its potential.

The conversations at FOCAS 2013 were positive steps in this direction. Here’s to citizens and civil society, entrepreneurs and technologists, venture capitalists and international donors, and governments the world over collaborating to advance equitable, accountable governance.

We are delighted to have Ashley Parent join our growing team as Office Manager. Ashley comes to Reboot fresh out of an intensive Arabic language program in Jordan. She previously held positions with the Clinton Foundation and Amnesty International U.S.A. Ashley will keep the Reboot house in order, managing day-to-day operations and designing key organizational structures across all teams.

This is the fifth installment of an Aspen Institute Communications and Society program series on equitable and accountable governance to be shared over a six-week period. The series draws on conversations from the 2013 Forum on Communications and Society to encourage constructive dialogue around open government.

Bemoaning government ineptitude is a popular pastime. There are times when it feels justified, but usually it just reveals our lack of understanding on how government works.

“Where are the public sector Foursquares and Twitters?” we ask. “Why hasn’t anyone developed a Kickstarter for government?”

The way the public sector is structured hugely constrains government’s ability to do so.

Rather than assuming what government officials are like and pontificating about why they are resistant to change, FOCAS 2013 participants—which included US and former UK government officials at the national, state, and local level—sought to understand their unique challenges.

“[In the private sector,] venture capital provides a dynamic and readily available source of funding to seed innovative initiatives,” explains management professor Sanford Borins, “while compensation through share ownership enables startup firms, their investors, their employees and, increasingly, their suppliers to reap large financial rewards from this activity.”

Compare this with the public sector where funding comes from legislative appropriations, civil servants don’t receive equity, and bonuses are comparatively tiny. Also in the public sector, the costs of failure—so often hailed by the private sector as a necessary step towards success—are unbearable. In a cutthroat political climate and unforgiving media culture, one misstep can end a career.

In short: the carrots are non-existent and the sticks are omnipresent. Put in their shoes, would you be able to ‘innovate’?

“We need to recognize the constraints that [civil servants] face and the culture that has been drilled into them: Minimize risks. A procurement officer’s job is to dot i’s and cross t’s,” said Clay Johnson of The Department of Better Technology at FOCAS. “Government is risk-averse for good reason. We’ve given it the responsibility of protecting taxpayers’ dollars.”

Despite the norms of conservatism, there are ways to enable new ways of thinking and doing. To do so, we must first understand how each government culture works. Just like with “citizens” and “communities”, “government” is not homogenous either.

The Boston Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics, recognized to be among the most innovative city governments in the United States, is a unique case. Susan Crawford recently studied the Office to try and dissect what made it so successful.

The secret sauce: leadership and people.

In an era where governments are eager to embrace the latest civic app, Boston Mayor Tom Menino favored human touch over high tech. He long refused to permit voicemail use in City Hall, because he didn’t want Bostonians to get an automatic response when they called. He opted out of adopting the standard, three-digit “311” number for his city services hotline—instead staying with the ten-digit 617-635-4500—because “311 sounded too bureaucratic…faceless.”

But each government institution has its own personalities, dynamics, and idiosyncrasies. What works in one place may not work in another. FOCAS participant Story Bellows of the Philadelphia Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics said her Office only gained credibility among other city agencies when it was selected a winner in the Bloomberg Philanthropies Mayors Challenge. While it had always had the support of the mayor, the internal institutional validation that was needed to get other agencies engaged only came with this badge of external recognition.

“Buy-in at the top was necessary but insufficient,” said Bellows. “Given the risks associated with doing things differently, we needed external validation of our ideas.”

Of course, not all cities are lucky enough to have Offices of New Urban Mechanics or Chief Innovation Officers. Some cities, as Caitria O’Neill of Recovers.org reminded us at FOCAS, only have Earl the Webmaster. And even if Earl had the time and technical skills, what would be his incentive to try and “open” his local government.

“In small communities, nothing hinders them from implementing open data,” said O’Neill, “but nothing encourages them or facilitates it either.”

At FOCAS, John Bracken of the Knight Foundation noted that several participants were “insider/outsiders”. These are individuals who had worked in government but were now outside, or former corporate or non-profit types that had recently joined government. He encouraged the group to use these unique perspectives to understand how we can enable government innovation. But given the diversity of institutional environments, political will, and resource availability, perhaps we should stop trying to create the perfect conditions for innovation. Rather, perhaps we should empower individuals within government to shape their environments to be more conducive to innovation.

“We haven’t yet had a conscious effort toward helping those working on the inside,” he observed. “How can we find mid-level managers and highlight their work? Can we help accelerate what they are doing by providing support and activating our and their networks?”

With these thoughts, the Government Innovator Cohorts concept was born. The program would support civil servants with a track record in driving public sector innovation. Ideally, fellows would be long-term civil servants that have both executive visibility and operational resources. Short-term political appointees would not be eligible, as they are typically installed to implement a new policy or mandate, and therefore likely to already have high-level support and ready resources.

Selected fellows would be giving skills training in technical (e.g. how to design effective programs), institutional (e.g. how to gain political cover), and managerial (e.g. how to implement public sector change) areas. The curriculum, however, while useful, may not be the key benefit of the Cohort program.

Several FOCAS participants had participated in similar programs. Andrea Saenz of Chicago Public Library is a Broad Residency alum and Jessica Lord of Github and Max Ogden are both former Code for America fellows. All confirmed that the greatest value of their respective fellowship programs was the peer support networks they gained. As Cohort fellows continue in their public service careers, having a network of like-minded peers with whom they can brainstorm, celebrate, and commiserate could be invaluable.

Many open government initiatives are driven by empowered citizens and civil society. This, in itself, is not a bad thing. But there is often an implicit negative bias against government in these initiatives.

In Dave Eggers’ “The Circle”, the main character, Mae, creates Demoxie, a platform where critical society questions are decided by citizen votes. She reflects on her creation: “[Mae] thought of that painting of the Constitutional Convention, all those men in powdered wigs and waistcoats, standing stiffly, all of them wealthy white men who were only passably interested in representing their fellow humans. They were purveyors of an innately flawed kind of democracy, where only the wealthy were elected, where their voices were heard loudest, where they passed their seats in Congress to whatever similarly entitled person they deemed appropriate. There had been some incremental improvements in the system since then, maybe, but Demoxie would explode it all. Demoxie was purer, was the only chance at direct democracy the world had ever known.”

The prose is eerily reminiscent of some of the narrative surrounding open government, rhetoric that serves demand-side goals well. This is narrative that unites organizers, motivates citizens, and attracts funding. This is also a narrative that can ultimately undermine open government.

In democratic societies, citizens select leaders for their vision and their perceived ability to implement those visions. In electing these leaders, citizens also entrust them to act in their best interest over the course of their term. Open government initiatives have the potential to displace a leader’s medium- and long-term plans for the needs of a loud and organized few.

In Uganda, the monitoring of elected community leaders has shown mixed results. On the one hand, some monitoring incentivizes leaders to work harder for their constituents. Too much, however, and competent, effective leaders quit.

As we work toward equitable, accountable governance, we need to balance between demanding transparency and participation and allowing our governments to do what we elected them to do. And we need to ensure our push for “open government” does not lead us down a path where competent leaders with technical expertise and long-term vision are upended by the immediate whims and desires of a small, elite faction. Otherwise, we’re right back to the image of the Constitutional Convention described by Eggers’ protagonist.

Recently I’ve fielded questions from several actors across the international development sector who are wondering what this whole “design” thing is about. The frameworks and concepts of human-centered design are increasingly finding a toehold. They haven’t been fully embraced yet, but there’s a lot of interest in how they might be utilized.

Of course, design thinking is still met with skepticism in parts of the development sector—and for good reason. High-profile examples of flashy gadgets like PlayPumps, SOCCKET and OLPC (especially in its early versions) rankle professionals in the development sector. Indeed, there’s much to scoff at when design is done poorly: by designers far removed from the end-users and their context, but nonetheless filled with assumptions about local needs, and funded by other outsiders who are more enamored with flashy technology than practical solutions. That’s a recipe for failure.

However, we’re starting to see that skepticism subside as the relevance of good, thoughtful design becomes clearer. I’ll admit to being a relatively recent convert myself. As I talk with think tankers and academics, practitioners and policymakers, I’m hearing that the frameworks resonate for two major reasons.

First, design research is inherently multidisciplinary. That makes it well-suited to complex problems that refuse to fit in easy boxes. When done well, it draws out a nuanced understanding of people and their contexts. This characteristic has allowed design to find relevance in a number of sectors. In development, where complexity and wicked problems loom large, the thinking provides a useful alternative to disciplinary silos.

Second, and even more important for development, the human-centered elements of design provide a critical counterbalance to the donor-driven incentives that often result in terrible development practice. The development sector faces countless systemic challenges resulting from the fact that funding comes from one place, while services or products go someplace else. This necessarily draws a strong accountability line away from those who are meant to benefit from the work. Design methods provide mechanisms for keeping our analytical focus on end-users, for operationalizing the empathy that we already feel, and for communicating the findings in a compelling (but still nuanced) way to donors or other outsiders.

These aspects mean that design can directly address some of the sector’s biggest challenges. As we’re starting to see more successful applications of design in development—such as institutional ethnography to understand service providers or iterative user testing for mobile applications—the sector is responding.

When talking with other development professionals, I try to include a word of caution: design thinking is no silver-bullet (nothing is) and it’s not magic. We consider it to be one tool in a larger kit. You can’t just sprinkle magic design dust on a problem and see it go away. But if you bring it to bear in the right ways, you just might unlock some insights and opportunities that were otherwise obscured.

P.S. Want to help us bring thoughtful design principles to development? We’re hiring.

Are we falling into a ‘buzzword trap’ around failure?

This question was on the mind of more than a few attendees at the FAILFaire “Fail to Scale” event, hosted two weeks ago by UNICEF Innovation.

Events like FAILFaire, platforms like Admitting Failure, and publications such as Stanford Social Innovation Review’s What Didn’t Work series are proving the old adage “failure is not an option” obsolete. We are recognizing that without failure, we lose the opportunity to learn why something didn’t work—“success goes to the head, but losing goes to the heart.” Failure hits hard and the knowledge we gain from it motivates change.

But while these events and platforms offer invaluable opportunities to open up about failure, how do we harness these discussions on failure to produce failure-informed change?

At FAILFaire, representatives from organizations ranging from UN agencies to social enterprises, media start-ups to design firms exposed their biggest project scaling failures in a 1-hour “Fail Slam”. Some used humor to make it bearable; others embodied the deep frustration failure has caused.

Most of the presentations fell into two general categories. In the first, speakers outlined the program, the failure, and the change that increased success. While helpful, these presentations were most useful for people working in a specific sector or geographic region. Jeff Chapin of CommonMade, for example, talked about his work with IDEO scaling up sales operations for latrine projects in Cambodia. He recognized failure in a sales model centered around Cambodian village health workers and reworked the model—as much as possible given funding constraints—to prioritize training and sustainability.

The second category of speakers focused on insufficient attention and funding from large donor organizations. Tala Dowlatshahi shared her main lessons on how to get attention based on her experience running Reporters Uncensored RUTV broadcasts on poverty and war. “Sex up content as much as possible, with celebrities, etc.,” she suggested to increase viewership. The co-founder of another organization had similar advice: “If you have Matt Damon talking about it, that’s success. That’s sexy.”

Across the board, discussions circled back time and again to deficiencies and constraints in our current systems: lack of attention from donors and intended audiences; inflexible donor funding structures and bureaucracies; the need to “work the system” with sex appeal or whatever is necessary to gain support.

Sexy sells, we know that. But sexy is not a solution.

The overwhelming focus of these discussions on ‘selling’ programs within existing structures trades short-term success for long-term failure because it concedes to the unresponsive systems that are at the root of the problem. Can we use knowledge from our failures to target the heart of the problem: the unresponsive systems themselves?

This is no doubt a far more intimidating challenge. As Jeff said, “We need a change in the system and I don’t know what that is.” FAILFaire is a positive step in this direction by providing a platform to talk openly and humbly about failure. As a next step, inviting program donor counterparts—large organization and government representatives—to engage in the discussion could help change the behavior of donors toward failure and the associated risks. More targeted discussion questions could help us go beyond frustration and placing blame to changing incentives and behaviors that aren’t currently serving those they should be.

Looking forward, let’s capitalize even further on opportunities like FAILFaire to discuss how we can begin to change the systems that enable our failures in the first place.

This is the fourth installment of an Aspen Institute Communications and Society program series on equitable and accountable governance to be shared over a six-week period. The series draws on conversations from the 2013 Forum on Communications and Society to encourage constructive dialogue around open government.

Among open government practitioners, The Citizen is a beloved topic of conversation. We love to talk about how The Citizen is frustrated, how The Citizen should be empowered, and—our favorite—how The Citizen will rise up to solve The Challenge.

But who are these mythical citizens? And, more importantly, what are they frustrated about, how will they be empowered and why on earth do they want to rise up to solve what problem?

At FOCAS 2013, Bryan Sivak of the US Department of Health and Human Services advocated for a more nuanced definition of ‘citizen’: “The term ‘citizen’ needs to be much more fragmented. For them to be an effective part of the open government process and to participate in enabling a cultural shift toward open government, we need greater definition and segmentation.”

Indeed, “citizens” and “communities” are not homogeneous groups. Each citizen or community has distinct aspirations, capacities, and constraints. To develop open government initiatives that citizens find useful, we must start with a more sophisticated understanding of those we seek to serve.

Open government, at its core, believes that citizens care about shaping the processes and outcomes of governance. Is this true?

A study on political engagement in the UK found that 86 percent of respondents believed political processes were in need of reform. Yet of the reform ideas they proposed, only 16 percent of respondents mentioned giving regular people a greater say in politics. While people want improved governance, they don’t necessarily want to be involved in improving it.

Around the world, evidence of citizen appetite for open government values is spotty. Recent Globalbarometer surveys show declining support for democracy throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, and the former Soviet Union. Even in Latin America, often touted as a hotbed of civic innovation, surveys found that 54 percent of respondents in the region preferred democracy to other forms of government, and only 28 percent were “fairly” or “very satisfied” with the characteristics of democracy. In many countries, including OGP countries Colombia, Peru, Brazil, and Mexico, either a minority or a small majority of people believe democracy is preferable to other forms of government.

Of course, variable faith in democracy does not mean a lack of support for democratic principles. But it does call into question our assumptions about citizen engagement in open government initiatives.

As Frank Hebbert of OpenPlans asked, “Why aren’t we building tools that transform the experience of being an engaged citizen?”

Surely, plenty of organizations have tried, but often they leave something to be desired.

Take the World Bank, for example, which has been committed to open data initiatives since its first Apps for Development Challenge three years ago. Then-President Robert Zoellick urged entrants to “help change the world by using the World Bank’s data collection to help find solutions to today’s development challenges.” Bank staff wanted to “build really useful applications addressing local problems.”

The winning app produces interactive visualizations of World Bank data. Second place was an app that measures progress towards the MDGs, and shows how events like war impact such progress. And taking third place was a tool that enabled people to rank different countries by their personal prioritization of development indicators. While the tools were useful, it’s unclear how they would “address local problems” for citizens in developing countries.

The Bank has tried to improve the accessibility of its tools to diverse user groups. One example is its flagship mobile apps, which lists the World Bank’s portfolio of projects, finances, and procurement data. The app is free, works without a data connection, and is available in nine languages on both the iOS and Android platforms.

That’s the good news.

The bad news? It is 30MB. In Nigeria, a country where over 60 percent of the population lives on less than a dollar a day, the app would cost about USD 3 to download. Accessibility is also limited by the fact that projects are listed by their Bank code, rather than program name. If a user searched for “Fadama”, an agricultural subsidy program with signs all over Nigeria, they would get a blank screen. Only by scrolling through all of the Bank’s listed projects in the country can a user find Fadama. And project finances are categorized as IBRD Loans, IDA Credits, and IDA Grants, without sufficient granularity to be useful to a budget monitoring activist or a community leader. In short, the app’s design limits its ability to “transform the experience of being an engaged citizen.”

In terms of user segmentation and effective design, we in the open government community have a lot to learn from the private sector.

No company worth its salt hawking a new product would claim “the consumer” as its market, and with good reason. A company has clear incentives to know exactly which consumers are going to buy which products through which channels. No market intelligence means no sale and no company. Granted, government agencies are obviously without these same incentives but the absence of market intelligence on the citizens that may use or benefit from an open government initiative yields the same results: no uptake and no open government.

Companies are also skilled in attracting and retaining users. They don’t take any user for granted. They design interactions and experiences that engage and delight, and they use sophisticated analytics to ensure their strategies are paying off. When they don’t, they change course.

Open government initiatives would do well to learn from them.

Fortunately, open government initiatives are increasingly attuned to citizen needs and behaviors. Outline, currently in beta, is a public policy simulator that allows citizens to better understand how government budgets and policies will impact them individually. For example, a household can visualize how a tax cut will affect its income or how a new healthcare bill may impact its health insurance costs. Outline pulls data from the Internal Revenue Service, the Census Bureau, and other government agencies and puts that data in context for regular people.

CivOmega is also trying to make open government less obtuse and more useful for people. This initiative allows people to ask questions about government in plain English—for example, “What bills did Eric Cantor sponsor?”—and provides users with answers, pulled from multiple open government datasets.

It’s no Siri just yet, but it’s a start.

Usability challenges include rigid syntax requirements for user queries. “What bills has Eric Cantor sponsored?” is incomprehensible. But the CivOmega team hopes to change that soon by incorporating natural language processing to enable a more intuitive user experience.

Ideas in Practice: The Public Experience Network

The Public Experience Network (PEN), a concept proposed at FOCAS, is a step in the right direction. The premise: many of today’s problems require collaboration beyond government and every citizen has some untapped expertise. So, let’s bring citizen expertise into government to help tackle public sector challenges.

This idea itself is not revolutionary. More interesting, however, was that not once were the words “crowdsourcing” or “new platform” uttered in the concept development conversation. Rather, FOCAS participants spoke of people they knew who might participate in such a program. They wanted to know why and how they might participate, and how government could keep them engaged.

Mark Meckler of Citizens for Self Governance described a friend who was passionate about mountain biking and would be eager to help design and maintain state parks. Alissa Black of the New America Foundation shared the story of an elderly African-American woman in California who had despised government all her life, but when asked to join in a citizen consultation program by her city, she became its most enthusiastic participant. Turns out all she had wanted was for government to ask for her opinion.

Once we understand who the users are, what they care about, and what their lives are like, we could then understand how to work with them. PEN would start by building a network of citizen experts through referrals who would be engaged in specific and discrete tasks relevant to their stated expertise. Participation incentives would be tailored to citizens’ unique motivations. Once the pilot is successful, PEN would experiment with how technology may support or extend existing processes. For example, both government offices and citizens could rate interactions they have with each other so reputations can be a part of structuring assignments.

So we’ve agreed to design solutions that suit citizen needs. But should average citizens be our target user? It depends.

Citizens don’t always have the means, technical skills, or motivation to participate in an open government initiative. Take, for example, Freedom of Information (FOI) legislation. Nearly 100 countries have implemented such laws, but their utility and impact have been hard to measure. Filing requests can be cumbersome and time-consuming, meaning citizens often tire of trying. Well-resourced corporations are instead the beneficiaries of FOI. Would resources be better spent helping the average citizen navigate FOI procedures, or would they be better put towards enabling journalists who have the professional motivation to chase hard-to-get data and the technical training to put it into context.

“It’s not enough to give people access to information,” said Evan Smith of the Texas Tribune at FOCAS. “We need intermediaries, such as journalists, to help citizens interpret information and to enable them to be able to act on information.”

Pierre Omidyar agrees. The eBay and Omidyar Network founder launched the Civil Beat Law Center for the Public Interest after he learned that government agencies routinely rejected journalists’ requests for reports, documents, and other information. The Center provides free legal help to journalists seeking to advance open government. His recent investigative journalism venture—founded with Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras, and Jeremy Scahill—is another vote for the role of journalists in ensuring citizens are able to benefit from open government, and governments are held to account for their promises.

Our fantastic communications intern, Andres Lizcano Rodriguez, landed a great piece on Colombia’s gender gap in World Policy Journal’s blog. Responding to incendiary comments by a prominent restauranteur in Bogotá about a rape that occurred at his restaurant, Andres argues that “beneath the country’s rosy modernization narrative is a disturbing tale of violence against women, violations of women’s rights, and entrenched gender inequity.”

Last month, Transparency International (TI) released The Global Corruption Report: Education. A corresponding World Bank blog post, written by one of the report’s contributors, poses the question at the heart of the report’s teacher absenteeism section: How can we help the “real losers…[the] students who yearn for an education but end up receiving no instruction?”

Both the report and the post share findings from multiple countries and discuss increasing monitoring and furthering research to decrease teacher absenteeism, one of the “most serious forms of corruption in education.”

Insights from the TI report include: absences often originate from inefficiency or corruption “upstream”; higher salaries don’t equate higher performance; supervision and disciplinary action could help reduce corruption; and, finally, these systems are failing children.

All of the above are true and worth noting.

But what is less clear in the World Bank post, and underrepresented in the TI report, is the fact that these systems are failing teachers, too.

Teachers stand in the line of fire. They are a highly visible bridge between policy and implementation, an easy scapegoat for underperforming education systems.

Addressing teacher absenteeism requires first understanding the teacher experience. As mentioned in TI’s report, understanding why teachers are absent, and the motivations behind their behavior, is crucial to making improvements. “Sanctioned” and “unsanctioned” absences are less black and white when we understand the pressures teachers face from governments, education boards, inspectors, families, students, parents, and countless others.

We recently came across this question within our portfolio of work in Nigeria. Since the 1970s, Nigeria has sought to provide universal primary education. But misalignments in political incentives, inconsistent lines of accountability, and marginal consequences for failed service delivery have all conspired to reduce the impact of this policy aspiration.

To better understand the causes of teacher absenteeism, we employed qualitative methods to understand the historical, cultural, and institutional factors that surrounded the issue. We engaged diverse stakeholders—from teachers and parents to community leaders and policymakers—both in schools and in their surrounding communities.

We found that a range of historical and systemic challenges within the education sector contribute to low teacher performance and absenteeism. These inefficiencies have left teachers as bystanders—instead of active participants—in the education system.

Public perceptions present one disabling cultural norm. Teaching has come to be viewed as an ‘all-comers job’, widely perceived as a career for second-rate civil servants. Those that choose it do so not out of desire, but out of necessity or convenience. Many teachers feel disrespected and unsupported, and they believe the education system places unrealistic expectations on them.

In terms of technical enablers for performance, teacher training—both preparatory and in-service—is ad-hoc, uncoordinated, and perceived as inequitably distributed. There is a gap between theory and practice in the responsibility for training, leaving teachers scrambling for information, resources, and organized support. The result is low morale among teachers. Combined with a lack of effective teacher management and oversight, these factors lead to high absenteeism and subpar performance.

The policy environment is also understood to place constraints on teacher performance. School assignments are perceived to be opaque and inequitable. When teachers are required to take postings in rural regions far from their families, this lack of inclusion and openness generates frustration and backlash. As one secondary school teacher told us, “I’ve been posted to this village for 14 years, but I know a teacher in [a city] that’s been able to hold on to her post for 24 years! Why can’t I request a similar posting or at least have the chance to rotate among areas?” Once assigned to a new posting, teachers must report for duty within one week, even if the new posting is in a distant, unfamiliar location. It is up to them to determine how they manage the impact of reassignment on their personal life. As a result, they feel powerless and demoralized.

The impacts of inconsistent public financial management also influence the classroom environment, a key aspect of the learning experience. Variable access to key resources poses challenges to teachers that constrain their technical ability to deliver and degrades softer aspects of performance accountability. When payroll is inconsistently met, some local administrators opt for staffing plans that optimize consistency over quality, resulting in some schools having student-teacher ratios as high as 100 to 1. When resources aren’t available for school inspectors, the dis-incentive for absenteeism is also reduced. It’s a two-way street: absences on one end influence performance on the other.

This is not to say that teachers hold none of the responsibility for teacher absenteeism. But our look at absenteeism in at least one region of Nigeria suggests that the accountability systems and improvements to institutional discipline desired in these reports are not addressing the nuanced drivers of this complex problem. While penalizing teachers may yield short-term improvements in teacher attendance, our research found that teachers actually perform better when they feel respected by their administrators and public audiences. Improving teacher performance is likely to require administrative systems that value the inputs of teachers as much as third-party evidence on their performance.

The TI report also acknowledged this viewpoint. Though it did not prioritize it against considerations of corruption, it noted:

“The social role and value of the school and teacher must be placed at the forefront of education policy and anti-corruption efforts. Teachers are often the first targets of corruption allegations, but this is often the result of corruption at the higher level and nonpayment of salaries or simple undervaluation of teachers. National policy-makers should understand the teacher as a role model and the school as a microcosm of society and train teachers to teach by example.”

If we want to help the students, we’ll need to understand and value teachers just as much.

If this is a defensible policy position, perhaps the question we should be asking is: how can our education systems positively reinforce responsible behavior among teachers and motivate them based on personal incentives? Initiatives focused on improving the performance of the education sector would do well by identifying interventions that: i) support teachers’ access to professional development; ii) inclusiveness and participation in key administrative decisions regarding assignments and tenure; and iii) levels of cultural validation for the importance of quality education in local communities. An approach that values the service providers as much as the service beneficiaries may provide unexpected gains to the opportunities presented to willing learners.

This is the third installment of an Aspen Institute Communications and Society program series on equitable and accountable governance to be shared over a six-week period. The series draws on conversations from the 2013 Forum on Communications and Society to encourage constructive dialogue around open government.

The central irony of open government is that it’s often not “open” at all. For all the talk of technology’s broad and inclusive reach, conversations on open government are dominated by those with the means to participate. In one Italian parliamentary monitoring project, participants were mostly men (84 percent) and 3,500 times more likely to hold a PhD than the average citizen. The priorities raised, as a result, represent the views of a narrow and elite group of citizens.

At FOCAS 2013, Kelly Born of the Hewlett Foundation asked attendees, which included senior executives from the Sunlight Foundation, the White House, and the Open Data Institute, “Is this [group of FOCAS participants] the right group of people to set goals for open government? Where are the citizens in this process?”

The practical result of those with power, privilege, and access tinkering for solutions while large citizen segments remain uninvolved is that open government initiatives are clouded by our own biases and tunnel vision.

We seek open government of the people, by the people, for the people—not open government by some people for some other people. To ensure open government does not become a hollow buzzword and lives up to the promise of its name, we need to recognize and address our biases.

With technology as such an obvious and visible driver of open government, the space is dominated by technologists with novel and creative ways to use their skills in the service of the public good. Gaps in their logic are given short shrift, as catapulting toward innovation is far more exciting than deliberating about unintended consequences. Hype-mongers and innovation-hawkers don’t help. And so government officials and civil society groups have been seduced by technology, by its novelty, and its capacity to relieve them from the hard work they have typically done toward social change.

While technologists’ passion has energized open government efforts and given them purpose, it has also left them willfully blind to alternative viewpoints. Do citizens and governments actually want this stuff?

“There seems to be an underlying premise [among the open government community] that government is open to being open,” said Mark Meckler of Citizens for Self-Governance at FOCAS. “But many governments are reluctant. We need to recognize this.”

Instead, technologists have often equated embrace of technology with embrace of open government.

Take Kenya, oft-celebrated as an open government success. Two years ago, the government launched the Kenya Open Data Initiative. At the launch, President Mwai Kibaki said, “I also call upon Kenyans to make use of this Government Data Portal to enhance accountability and improve governance in our country. Indeed, data is the foundation of improving governance and accountability. . . . This way the people can hold government service providers accountable for the use of public resources.”

The Initiative has neat apps, a Twitter account, a Facebook page, and has enabled the Code for Kenya program. In 2012, Kenya joined the Open Government Partnership.

In that same year, however, at least 28 journalists were threatened or attacked by government bodies for their coverage of state corruption. And today, the country is considering legislation that would further tighten media regulation—already described by local journalists as “emasculating.”

A technocentric view means that as long as a government embraces new technologies, releases some datasets, and makes high-profile commitments to the international community, it is a card-carrying member of the open government community. Whether the government actually allows its citizens to freely and openly use open data is apparently irrelevant.

So what does it mean that 62 countries have joined the Open Government Partnership? On its own, not much. To move beyond our biases, we need to stop chasing white whales and refocus our thinking toward a more humble target.

“New techniques, not just new technologies, are important in advancing open government innovation,” noted Andrew Stott of the UK Transparency Board. He should know. Stott led the work to open up UK government data and create Data.gov.uk. And in his experience, the means are just as important as the ends.

Innovation is, very simply, “a new method, idea or product.” Approaches to innovation should differ based on when, where, and how that innovation is expected to have an impact. Leading CEOs advise against blindly pursuing breakthrough innovation—in many contexts, incremental innovation is the better option.