Last year, we hosted four incredible interviews with folks driving radical collaborations across the globe. Our world has transformed so much in the time since, but the wisdom of these great leaders sustains. Take a listen.

We are actively engaged in the dialogue and debates of our space: on issues of social justice, global development, and democratic innovation, and on the ethics and methodological evolution of design, mediation, and co-creation practice. More of our writing can be found at Medium.

“Multi-stakeholder approaches,” “participatory development,” and “design with the user” are increasingly popular concepts in global development. As an organization founded on the belief that citizens should have a greater say in the policies that affect their lives, we at Reboot should be heartened by this momentum towards greater collaboration with “users” and “beneficiaries.”

But too often, we’ve seen co-creation done poorly. Many organizations have recognized the importance of collaborating with the diverse stakeholders who will be touched by the policies or products they develop, but rhetoric rarely matches reality. Co-creation is hard. With more voices in the room, the process is slower and more complex; it can seem impractical. And let’s be honest: co-creation decreases the influence of powerful actors in shaping outcomes. The development industry often lacks both incentives and mechanisms to co-create, and as a result, it isn’t often done well.

These concerns were at the top of our minds when we learned that USAID and Sida—the American and Swedish international development agencies—wanted to convene over 60 people from 50 organizations to “co-create” an ambitious new program to support and strengthen civil society around the world.

Globally, advancing social justice and human development often relies on local civil society organizations. Yet the right to meet, organize, and drive change through civic action is facing backlash. Since 2012, the International Center for Non-Profit Law has documented more than 50 countries seeking to ban or constrain civil society activity.

USAID and Sida are two of the founding partners around a new initiative—launched as part of President Obama’s global call to Stand with Civil Society—that aims to combat this growing repression, expand civic space, and strengthen civil society. They plan to do this by developing a network of regional civil society hubs, each tailored to the goals and needs of civil society communities in that region.

In a laudable demonstration of donor humility, USAID and Sida admitted at the outset of our collaboration that they didn’t know the best way to create these hubs. This honesty created the conditions for a true co-creation process. Rather than designing a program from the top down then validating it through consultation, USAID and Sida aspired to work with civil society actors as true partners.

And so they issued a global call for ideas on ways to support and strengthen civil society. Over 200 organizations shared their ideas, and over 40 were invited to a co-creation workshop in November 2014 in Istanbul to set the ethos and foundation of a new initiative. Reboot and CIVICUS, a global alliance of civil society organizations, were asked to join, both as participants and to design and facilitate the workshop.

How to get participants to let go of their standard ways of thinking and doing?

How to get participants to invest in addressing the challenge without being biased by their own incentives and potential individual returns?

How to challenge traditional power dynamics so that solutions can benefit from the wisdom and experiences of all assembled?

How to quickly establish a collaboration model that respects all voices and inputs, while empowering the group to take practical and timely decisions?

At its heart, co-creation is about bringing people together to develop solutions to a common challenge. While this sounds straightforward, what makes it tough is that actors almost always have different perspectives on the challenge, different levels of experience addressing it, and different interests and motivations for engaging in the work.

Power imbalances within the group make working through these differences towards constructive solutions all the more difficult. While power and politics naturally plays into any group’s dynamic, facilitators must carefully navigate these imbalances to bring forward each individual’s perspective and expertise.

Too often, exercises billed as co-creation fail to live up to their stated values of inclusivity, leaving repeat participants wary of such “consultation as insultation” processes. Understanding this, it was no surprise to hear participants at the start of the Istanbul workshop wondering aloud whether the donors had brought a plan to be rubber-stamped, and if the workshop was simply a political box to be checked.

Crafting effective co-creation is much like designing any program, service, or product. “Just do a workshop” is a short-sighted mistake. A thorough process and strong user experience design are critical. Our team worked closely with USAID, Sida, and CIVICUS before and after the three-day Istanbul event to optimize participant experience and, in doing so, harness their expertise into productive outcomes. Recognizing the unique dynamics of this design exercise, we relied on a set of core principles to guide our work.1

Break out of established roles and mindsets. As with most such gatherings, there were power imbalances within our group, which included both donors and grantees, as well as representatives from the global North and South. To break with traditional hierarchies, we had to force participants out of familiar roles and mindsets.

To do so, we first worked to understand the interests, experiences, and expectations of each co-creator. (This was especially critical given that many civil society actors, while they may be ideological allies, are commercial rivals, competing for a pool of limited resources to do their work.) What does a human trafficking activist in the Philippines and a freedom of information lawyer in Georgia have in common? On the surface, not a lot. But throughout the process, we asked participants to bring their individual experience to the fore, rather than calling on them as representatives of their organizations. By asking participants to recognize the respect for human rights that unified us all, they were able to shed their “organizational hat” (and the associated pressures) and collaborate towards a common vision.

We framed conversations to draw on the experiences of less-privileged voices, and asked the more-powerful actors to be transparent around their interests and resources. Donors, for example, had to answer sometimes uncomfortable questions about organizational politics and funding that may impact the initiative. They were also asked to be highly sensitive of their influence in group settings, and to participate by asking clarifying questions rather than offering opinions that might overly sway the conversation.

Define the “what” and allow creativity around the “how.” Facilitating a co-creation process is about articulating a vision, establishing the parameters, and guiding participants to a shared definition of what success looks like. It’s never about the specifics of execution—that’s up to the co-creators. And while we designed a detailed implementation plan with multiple possible paths, these were used as flexible scaffolding rather than fixed itinerary.

Around the “what,” we recognized that USAID and Sida had given us an intentionally broad mandate. And so, to focus our thinking and encourage rigor in both thought and action, we unpacked development buzzwords and fuzzwords to understand what each of us meant by terms like “increased impact” and “inclusive participation.” This primed us to be clear about what it was that we sought to achieve.

We asked participants to draw on their own experiences to develop success criteria that were familiar and tangible, rather than based on abstract principles or case studies. The group jointly aligned on a set of key “nuts and bolts” (e.g. service offerings, business model) that designs of the hubs should include. This gave participants categories and boundaries within which to design, while also providing leeway to create locally tailored content.

And we stayed flexible and adapted schedules and exercises as we went along. Because when you give 50-odd very opinionated people a big, hairy task, you need to be ready to seize the opportunities (and address the challenges) that come out of it.

Build an invested community of collaborators. Successful co-creation efforts are the work of a cohesive community, not a collection of individuals. Collaborators must build trust before tackling the technical challenge at hand.

We designed the co-creation process around anticipated human dynamics—such as past relationships or histories that may have caused reservations—seeking to first build unity, then “do the work.” Thoughtfully designed icebreakers, high-energy exercises, and social activities were critical for building community bonds. An open spaces session allowed participants to talk about whatever they wanted, even if it was outside the meeting’s scope. We monitored the human factor throughout and adjusted activities accordingly.

Some of this, understandably, worried the convenors—would the work get done in time? But by late the second day, when we had given the final co-creation assignment, participants were rearranging their evening plans and setting 7am breakfast meetings. Most of us wouldn’t do that with our colleagues or fellow workshop participants—we only invest in such a deep, personal way when we’re working alongside comrades.

Participants left Istanbul buzzing with levels of energy rarely seen after being crammed in a conference space with too many strangers and too little elbow room.2 Rich conversations continued online in the following months and have now led to the foundation of a truly innovative global initiative to support civil society.

At Reboot, we are proud to see our design and facilitation methods help mitigate conventional power structures, putting authority and ownership in the hands of users—in this case, activists, civil society actors, and their supporters advancing social justice around the world.

USAID, Sida, and several co-conspirators are now planning regional design processes, where this initiative will make more concrete decisions on how to support civil society innovation in each region. We look forward to updating you as it moves forward.

____________

1: To dive further into the process we used to create the Istanbul workshop, see our briefing note Co-Creating the Civil Society Innovation Initiative: Process Journey from Idea to Design (PDF, 518KB)

2: For more on both this workshop and the broader initiative, see blog posts from the US Institute for Peace and USAID, and the Civil Society Innovation Tumblr.

The latest issue of the Kuramo Report, a Lagos-based quarterly publication on the intersection of business, policy, and development, features Reboot’s work creating citizen-driven improvements to public services in Nigeria. In partnership with the World Bank and local government and healthcare officials, Reboot designed and piloted a patient feedback platform in Wamba, Nigeria.

We are delighted to announce that Husna is joining Reboot’s team as the new Director of Programs. She brings valuable experience leading programs in conflict-affected

At EduCon, a conference on the future of schools, Zack will present on the theme of connections, drawing from Reboot’s work around the world to discuss how globalization connects communities and advances opportunity, but also exacerbates inequality. In Philadelphia, January 23–25.

Panthea will present Reboot’s work in Nigeria and elsewhere on a panel on strengthening collaborative governance, while Adam will lead a discussion on public infrastructure service delivery. The conference will take place from January 16 to 18 in Montreal, Canada. Follow #unitetounlock, @PantheaLee, and @AdamTalsma for coverage and updates.

Brought out in handcuffs, a defendant stands with his public defender before a judge. The prosecutor requests that bail be set at $500. The defendant has a warrant on his record—likely the result of a failure to appear in court—and so the non-profit that provides bail recommendations advises against releasing him. If the judge agrees with the prosecution’s $500 request, the defendant, a day laborer, won’t be able to afford it. He will be sent to Riker’s Island prison to await his trial date, a few days or even weeks away. He will lose his job for missing work. He will not be able to pick up his children from school or watch them in the evening. This man has not been found guilty of any crime, nor has he had a trial in front of his peers. Yet his life will be turned upside down by even the briefest stint in prison.

His alleged crime? Putting his feet up in a subway car.

While much of Reboot’s work takes place overseas, we see too many instances of injustice and abuse in our hometown, and we focus our pro-bono work here in New York City. In the past, we’ve worked with the domestic violence organization, Safe Horizons, to design communications materials to better reach trafficking victims. Right now, we are deep in a project with a new organization, the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, aimed at designing an immediate solution for one of the most systemic economic inequalities in our courts.

For this project, we’ve spent several days viewing arraignments in King’s County Courthouse, and have seen many heart-rending stories of people unable to post bail. Studies from Human Rights Watch and others confirm that bail is a common source of inequity and discrimination in the criminal justice system. Most people who can’t afford bail end up pleading guilty, forgoing their right to a trial just to get out of prison and go home. The system needs to change, and many public defenders believe that the cash bail system should be abolished completely.

But on the way to reform, small nonprofit organizations like the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund are stepping in to give more defendants the benefit of release. This fund will post bail for people charged with low-level crimes, allowing them to continue working and caring for their families while awaiting trial. After watching the wheels of Brooklyn’s misdemeanor court turn, we know first-hand how much this program is needed.

Bail often punishes low income people for crimes they have not been found guilty of committing. A short time in jail can have massive repercussions for anyone, but especially for those living and working without a safety net, at the margins of society. Homeless people often lose shelter housing, for themselves and their families if they are unable to show up for an evening. People in low-paying and temporary jobs will often be fired if they fail to appear. Those receiving treatment for drug addiction may face serious health risks if a program is interrupted.

Bail is intended to ensure that people charged with crimes return to have their day in court. But in practice the system does just the opposite, often forcing people to plead guilty. The public defender organization Brooklyn Defender Services recently collected data from a sample of defendants in Brooklyn; in that group, an incredible 92 percent of defendants held in prison pled guilty, as opposed to 40 percent of those released on bail. The desire simply to return home is a powerful incentive to forgo one’s right to a trial.

Even if a defendant perseveres, simply having been unable to afford bail negatively affects the outcome of the case when it does go to trial. In the same group of defendants, only 38 percent of those held on bail received a favorable resolution, compared to 88 percent of defendants who were free leading up to the trial. The bail system clearly works against the basic tenet of innocent until proven guilty.

Inability to post bail even when the amount is very low affects thousands of New Yorkers every year. In 2008, the defendant was unable to afford bail in 87 percent of cases in which bail was $1,000 or less —this translates to over 15,000 New Yorkers held in prison for an average of 15 days before trial. The consequences extend to taxpayers as well: According to Human Rights Watch, the average daily cost for each incarcerated inmate is $400. Nationwide, the estimated cost of imprisoning people held on bail reaches $9 billion each year.

Fortunately, a growing number of bail funds are providing a temporary solution. Although the number of bail funds is still relatively few, they exist in several states, including New York, where a 2012 law sanctioned nonprofit bail funds for the first time. The success of these pioneering programs offers strong proof that we need more like them. One inspiration for the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund is the Bronx Freedom Fund, which boasts a 98 percent return rate for bail fund recipients. That’s higher than the rate of return for those released without bail.

Reboot has been studying the example of the Bronx Freedom Fund as we work to support the best possible design for Brooklyn’s fund. We are working closely with public defenders involved in the establishment of the fund, as well as the Board of Directors that will oversee it once established. Our mandate is to bring expertise in design research to help build a system that will reach the defendants who will benefit most—and one that administrators can manage sustainably.

Our project has required in-depth field research with the justice system. Observing arraignments in court improves our understanding of the people involved in a court case: What pressures are faced by public defenders, who are the front-line in serving clients? Interviews with public defenders reveal important opportunities: What can they teach us about making sure defendants show up in court—since they’ve been doing it for years? And interviews with people who have faced bail themselves help us understand how a bail fund can better serve people like them.

Bail is a serious impediment to justice in this country—one of many in a criminal justice system rife with discrimination and flaws. As New Yorkers, we’re hungry for change, from the NYPD to the courts. As designers, we know that reform requires empathy and listening to succeed. As we work with the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, we’ll continue sharing insights here in support of design for a better justice system.

We’re excited to be partnering with Be Social Change to ring in the holidays and build stronger connections between the people and organizations driving social innovation in NYC. This evening at 6:30 PM, join us at Wix Lounge for the New York Social Good Holiday Bash. Bring your friends for an evening of festivities with a community of purpose-driven entrepreneurs, professionals, and creatives. Reboot friends get a 25% discount with the code “NYSGholiday.”

The international development sector has a history of expensive failures. Top-down planning, marginalizing local actors, transposing cookie-cutter solutions from other contexts, and short-term “band aid” solutions are all to blame for these projects’ lack of impact.

Against the backdrop of these failures, a number of projects are successfully creating real change. Even within the same systemic constraints, these projects have found ways of doing development differently and creating impact. They are positive deviants within the sector.

In October, Zack and I had a chance to take part in an event focused on those positive deviants. Hosted by the Overseas Development Institute and Harvard Kennedy School, the two-day workshop, “Doing Development Differently,” sought to build common understanding and a community of practice around a new way to engage in international development.

Learning from positive cases was central to the event. Over a dozen practitioners and policy makers presented focused case studies: seven and a half minutes, no slides, just the story. These case studies, complemented by the experience of participants, fed into broader sessions aimed at teasing out common principles.

In the weeks since, the conveners and participants have crafted a manifesto. It states that successful initiatives tend to follow common principles:

They focus on solving local problems that are debated, defined and refined by local people in an ongoing process.

They are legitimised at all levels (political, managerial and social), building ownership and momentum throughout the process to be “locally owned” in reality (not just on paper).

They work through local conveners who mobilise all those with a stake in progress (in both formal and informal coalitions and teams) to tackle common problems and introduce relevant change.

They blend design and implementation through rapid cycles of planning, action, reflection and revision (drawing on local knowledge, feedback and energy) to foster learning from both success and failure.

They manage risks by making “small bets:” pursuing activities with promise and dropping others.

They foster real results – real solutions to real problems that have real impact: they build trust, empower people and promote sustainability.

Reboot was happy to sign on to this manifesto because it ties so closely to how we already work. In fact, Zack presented our work on social accountability in Nigeria at the workshop, and our friend Natalia Adler from UNICEF talked about the project that we did with her team in Nicaragua. The manifesto also draws from a pioneering array of methods, experiences, and principles presented by other participants who shared their work, including the “problem-driven iterative adaptation” (PDIA) approach used by Matt Andrews and others at the Kennedy School’s Building State Capability program.

The community of practice resulting from the workshop is carrying the initiative forward. The event drew an influential group of 40 participants together, and facilitators managed to create more engaging discussions than you typically see at a policy workshop. Several people commented that they had been trying to drive change in their own institutions, and that this group finally made them feel that others were dealing with the same struggles. Oxfam’s Duncan Green called it “two mind-blowing days.” We left feeling invested in the next steps.

However, challenges lie ahead. First, this community of practice needs to grow. We need a larger community to infiltrate more development institutions and change policies as well as mindsets. Even more importantly: We need more diverse perspectives to better articulate these principles and develop a deeper understanding of what they mean in practice. The “Doing Development Differently” workshop skewed heavily Northern, with few voices from the global South in the room. It was also dominated by donors and consultants. If that lack of diversity continues, it will impoverish our ideas and our impact.

The need for diversity relates to another challenge: incorporating power and politics into these principles. The Northern/donor perspective at the workshop led us to frame issues from the standpoint of outsiders promoting or funding reform or direct services. The resulting principles call for more agency and leadership from local conveners. However, I suspect that the needed shift in relationships is more nuanced. True success will involve different types of approaches on the part of local actors; and all of these relationships are tied up in politics and the specific individuals involved. This is a thorny set of issues.

Finally, this community needs to present something truly new, useful, and impactful. One critique raised at the workshop, and readily acknowledged by the conveners, is that all of these ideas have been floating in the development sector for some time. This community of practice may be able to offer something unique if it can solidify and operationalize these principles in various development institutions (to this end, we discussed issues like procurement and human resource policies). But institutionalizing the principles carries a risk of watering them down, as often happens when issues or approaches are “mainstreamed.” Even the logframe, that favorite punching-bag for development reformers everywhere, started as a well-intentioned effort to improve planning.

Despite the challenges, I’m optimistic about these efforts. Later this week, I’ll be in Berlin for a meeting hosted by the World Bank and Germany’s aid agency GIZ that will build on the workshop and the manifesto. The next stage involves creating more robust case studies, beyond the seven-and-a-half-minute presentations from the workshop. We’ll seek to craft a case study methodology that incorporates local perspectives and lessons—and that captures lessons about emerging practices in an actionable way.

The work of changing institutions is hard, but we’re happy to help drive these efforts forward, in theory and in practice. Ultimately, doing development differently means ensuring that the “positive deviants” become the norm.

_____________

Resources:

This afternoon, Dave will judge Columbia SIPA’s New Media Task Force Pitch Competition, which in its 4th year focuses on digital technology solutions for the global urban environment. Pitches from competing teams will propose ways to improve urban waste management in India, eldercare in China, and postal services in Kenya. He will be joined by co-judges Robert Fabricant of Dalberg and Anand Shah of BMW Impact Ventures.

We are pleased to welcome Laura and Anna to the team. Laura Freschi comes from NYU, where she worked on aid effectiveness, development history, and financial inclusion. She will join Reboot as Director of Partnerships, overseeing our in-house communications and creative team, and leading Reboot’s efforts to spread its philosophy and learning through writing, events, and partnerships. Anna, a social innovation specialist with a background in neuroscience, social justice, and human-centered design, will contribute to strategy, research, and development of products and services.

Reboot will have several team members in Istanbul next week for a Civil Society Innovation Initiative co-creation workshop. USAID and Sida are convening over 40 civil society organizations from around the world for the three-day event. Reboot is both a participant and also facilitator, along with our co-facilitation partner CIVICUS. Follow along on Twitter – #CivSocInov8

At Reboot, we take thousands of photos over the course of a project. We take pictures of people and their environments—homes, workplaces, possessions, and the list goes on. Photography has always been an important part of our research and data gathering process. Imagery serves as a critical visual tool, and one that helps foster empathy for those we are working with.

Imagery is also a key component of Reboot’s visual identity, as you may have deduced from this website. Images of people are especially powerful in revealing the details of the kind of work we do, the people and places we learn from, and the principles we stand for. But using someone’s likeness publicly—anywhere—means we need to do so in a respectful and responsible manner.

For anyone that has taken a passing look at many socially-oriented organizations, especially in the international development space, you know well that this is not always the case. “Poverty Porn” abounds on the promotional materials for everything from large NGOs, to small consultancies, to personal work portfolios and photographers’ websites. Big teary eyes, small tattered clothes, images of want and famine that pull on your heartstrings. Oh, it’s in Africa? Even better.

These are images that capitalize on viewers’ sympathetic or pitying emotional reactions, and which they use for a reason. Sympathy and pity are strong emotions, they prompt strong responses—all the better for drawing attention to your work and especially for fundraising. But what do they do for the people featured in the photos? They didn’t ask for our sympathy, they didn’t ask for our pity.

At Reboot, we work to empower and to enable. A visual world of sympathy and pity doesn’t sit well with us as people, and it surely doesn’t sit with the mission of our organization. So, we chose a different approach.

First and foremost, we recognize that as the individuals who document, process, and use images of other people we have responsibilities, namely:

This means we leave a lot of images on the cutting room floor. Out of the thousands of photos taken over the course of a project, only a very select few are seen by anyone outside of the Reboot team. In fact, when it comes to showing the rest of the world the work we do, out of those thousands, we are often limited to just a handful of photos to represent the months (if not years) of work that went into each project.

To ensure that we practice what we preach and live up to our responsibilities, we’ve implemented a system of ensuring that individuals are informed about how their images might be used, and asked for their permission to use their image in these ways. Those permissions or denials are then recorded and tagged in the photo’s metadata. Beyond seeking informed consent, we also defined the ways we should and shouldn’t use certain types of images, especially with regards to the appropriateness of using images of people.

Distinguishing between images that are used internally for research only and images that could be used externally—on the website, research reports, or elsewhere—proved helpful to realizing this system. Where a photo of a person is used to draw a direct connection to an individual, place, or context, using that image makes perfect sense. But where a photo of a person is used only to draw a connection to ‘corporate’ Reboot, this doesn’t fit well with our values. We need to be aware of the fact that we are essentially facilitating an introduction to these people through their imagery, and therefore must be more intentional about how we tell their story when we do use images of people in our corporate communications.

Addressing this relies on a combination of written copy, design elements, and photo choice. For example, on promotional postcards given out at events and info sessions, we incorporate a short sentence on the reverse side of the page that provides a brief description of that person and tells where to find out more about them (i.e. a link to a case study on our webpage). Doing this creates more context for understanding between the viewer and the individual shown, and also allows us to form stronger connections within our own work and materials.

In cases where the format doesn’t allow for us to add more information, such as a business card or other small canvas items, we shift to images of people where the individuals are more anonymous. In this way, we avoid establishing a false sense of empathy, where the viewer feels a strong connection to the person, but can’t learn more about them to truly understand their context.

Most importantly, we didn’t force this system out of thin air. Rather, it came about organically and sustainably as a product of our values. While more time and difficulty is added to taking, processing, and using our photos, the fact that we as an organization decided to do it this way engenders support among the team. Having these beliefs arise from our staff organically meant that on the whole, these guiding principles had already been informing our image choices all along, even before it was “official.” By formalizing these ideas, we made ourselves, our clients, and the communities we were working with a promise that we are keeping.

We officially put this approach into practice exactly one year ago and are still working backwards to update older materials to be in accordance. It’s not perfect yet, but we’re on the road. Our hope is that by sharing the lessons from our experience, we can encourage other mission-minded organizations to take a look at their own photo use policies and ensure that they practice what they preach.

___________

A partial list of some of the resources we found helpful along the way:

Zack and Dave are participating in “Doing Development Differently” on October 22nd and 23rd. The event is jointly hosted by Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and the Overseas Development Institute. They’ll be presenting Reboot’s work on public financial management reform and facilitate a design-thinking workshop. Follow #differentdev on Twitter for live coverage.

Kerry will moderate a panel at this year’s ConDatos on October 1-2, the most important regional event on open data in Latin America and the Caribbean. The panel will feature Latin American and Caribbean open government specialists discussing how to design initiatives that enable institutional participation and integration.

Two interesting trends have recently been coming together in an exciting way: the push for open data, and the “Learn to Code” movement. Together, they show great promise for realizing the goals of open government, but this promise has yet to be fully realized.

Open data has increasingly become a way for governments to demonstrate their commitment to transparency and accountability. Calls to release government data have been heeded to varying degrees by local, provincial, and national governments in many countries. And open data is, in itself, no small feat. Releasing data in any capacity is often an immense hurdle, and one for which governments should be recognized.

But, as anyone who has ever downloaded spreadsheet upon spreadsheet of government data (or pored over printed table upon table in a government publication) can tell you, open data alone does not automatically equate to open government. Open government requires citizens and governments to interact with open data and transform it into something that can drive debate, advocacy, and accountability.

Two weeks ago, I had a chance to see the challenges of converting open data into open government firsthand in Indonesia. The Indonesian government has been pushing to increase the adoption of “e-procurement” nationwide as part of its open government strategy. In this system, companies that want to win government contracts must submit their bids through an online process, which facilitates monitoring. The government then publishes data on the open calls and winning contracts.

But even governments whose processes are largely computerized typically store data in formats that serve their purposes, not the needs of the citizen user. For example, when the government of Indonesia first began releasing data, it had to be downloaded by an individual procurement package. More importantly, the data in its raw format is not immediately meaningful to most citizens.

This is where the Jakarta-based Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) saw an opportunity. ICW works with the Indonesian procurement agency, LKPP, to consolidate their data on e-procurement on the website opentender.net. Visitors to the site can visualize data and search for contracts with specific characteristics. That would be valuable itself, but ICW went a step further by developing a tool called Potential Fraud Analysis, which applies a scoring algorithm to procurement contracts in order to identify those with a higher likelihood of fraud. Armed with this data, civil society groups, journalists, and citizens can then undertake further (analog) investigation in order to hold government units accountable for their use of resources.

The implementation of open data initiatives is often midwifed by civically minded programmers who write the code to display government data online. Efforts like those of ICW’s staff demonstrate the importance of computer programming skills in ensuring data accessibility, but these skills are still uncommon. The languages that underpin the ubiquitous websites and applications that have become a part of everyday life for many people around the globe remain a complete mystery to most of us. Fortunately, there are efforts underway to change that.

The Learn to Code movement is seeking to de-mystify the computer programming process in an effort to put technological tools in the hands of more people. There are various “learn to code” online courses like Code Academy, while groups like Girls Who Code are working to build up communities around tech skills, with a focus on groups that are underrepresented in the tech industry. This fall, students in UK schools are being taught from a new computation curriculum that includes ambitious computer programming coursework for students starting in primary school. These courses focus on teaching languages like HTML, Python, javascript, PHP, and Ruby on Rails (to name a few), in the service of web design and skills needed to work in the tech industry.

This is where I want to make a pitch for another kind of coding that I think is at least as important for citizens around the globe: coding for data analysis. Learning to code websites and applications is an essential skillset for visualizing and publishing open data online. But statistical analysis is what allows us to interrogate, test, and extract meaning from data, and many powerful data analysis applications (including open source options like “R” and other popular programs like Stata) rely on the use of command lines or formulas.

Learning a few key lines of code in one of these applications (and, more importantly, how to interpret the results they produce) opens the door for anyone—not just academics or researchers—to identify statistical trends and relationships related to the issues faced by their communities. It puts real power and flexibility in the hands of citizens to test the claims they hear from those in power and to back up advocacy with hard facts. Data has the potential to inspire powerful stories, but these stories must be unlocked through analysis.

This week, I’m in Mexico City for Condatos, the Latin America Regional Open Data Conference. The conference is an exciting example of burgeoning efforts to integrate programming, data analysis, and communication of open data. The agenda includes speakers and discussions with policymakers, entrepreneurs, researchers, data scientists, and data journalists, all of whom will be talking about the future of the open data ecosystem in the region. On the day before Condatos, the AbreLatam “unconference” will offer workshops and experiences such as a Data Bootcamp that will bring together 20 journalists, 20 programmers, and 20 designers to learn how to analyze and visualize open data. I’m looking forward to seeing firsthand some of the latest efforts to turn open data into truly open government.

Dave will moderate a panel at the World Summit on Innovation and Entrepreneurship on September 29-30. The panel, titled “Market-Based, Risk Capital Funding for Peace”, will explore how to develop a market-based “peace industry”.

This Friday, September 26 Zack will give the keynote speech at the 2014 PakathonNYC. The event connects technologists, entrepreneurs, and development professionals to explore how technology can address social issues in Pakistan. Zack will talk about Reboot’s experience applying technology for development in Pakistan and elsewhere.

Last time I wrote about Mexico’s Agentes de Innovación program, the teams had only just begun the co-creation process that the program hopes to encourage. Over the past several months, the teams have been hard at work further defining the problems they want to tackle, and beginning to ideate around potential products that they might develop.

Each of the teams was initially assigned an (ambitious) overarching theme taken from the country’s National Digital Strategy, which they then narrowed down to (almost-equally ambitious!) driving questions. During the first months of the program, the teams were asked to apply the human-centered design methodology to their issues by undertaking research on the needs of their target users. The projects have continued to evolve based on this research, as well as ongoing conversations within each of the host agencies and the teams’ considerations of priorities and constraints.

Here’s a rundown on the latest updates from the different teams:

The Universal Health team is working within IMSS, The Mexican Social Security Institute. They are asking, “How, through social innovation, can we bring IMSS services closer to the citizen?” In particular, they are focusing on the experience of maternity care for women at IMSS clinics. Maternity care at IMSS isn’t only for those women who expect to deliver at an IMSS clinic. Many more than that attend clinics for pre-natal visits, as it is a requirement that working women must complete to request official maternity leave benefits. The team is hoping to tackle both the administrative process and the care received by patients.

The team focused on Citizen Security is linked with the Ministry of the Interior. Their team is asking, “How can we involve citizens in the prevention of violence?” This team’s intervention is based on an existing platform, CIC, which allows citizens to anonymously report everything from traffic to criminal activity and has had great success in Monterrey, Mexico.

The team taking on Governmental Transformation is housed at the Finance Ministry, specifically within the group responsible for performance management of programs that are part of the federal budget. The team is asking, “How can we integrate levels of satisfaction and feedback from citizens on budgeted programs into the evaluation of their performance?” They will develop a way for program beneficiaries to provide feedback on the programs they use.

The Digital Economy team is based at the National Institute for the Entrepreneur. Given this affiliation, the project is focused specifically on the National Entrepreneurs Fund, which has a budget of nearly 9.4 billion pesos (over 710 million USD) for 2014. Their team has identified a need to improve entrepreneurs’ experience of the fund’s application and tracking process. They are asking, “How can we create a system for the Entrepreneurs Fund that facilitates and makes transparent the process for Mexican entrepreneurs?”

The Quality Education team, whose internal Agente works in the Educational Television section of the Ministry of Education, asked the question, “How can we rethink distance education based on new technological tools?” The team has decided to focus on the issue of students who are at risk for dropping out of school, and how they might be supported and inspired outside of the classroom.

Each of the teams has undertaken user research in their own way. As part of our own process, the Reboot team did some user research of our own in order to have a benchmark that we might use to better understand the teams’ design processes and decisions. In a wide-ranging (but, at only one week long, unusually short) research sprint, we conducted some 50 interviews across five locations.

We spoke to citizens relaxing in Puebla’s main square about citizen security, expectant mothers in Toluca about their experience of maternal care in primary clinics within the Mexican Social Security healthcare system, high school students in Mexico City about their expectations for the future, and entrepreneurs attending the “Week of the Entrepreneur” event in Mexico City about their experience accessing financial and other support.

Besides some intriguing findings for each of the individual projects, we were also left with some questions that we think are relevant for many in the sector trying to incorporate innovative processes.

When is the appropriate time to introduce technology to an innovation process? The great potential of technology can make it tempting to start with the assumption of a technology product or platform. When the real pain point is systemic or policy-related, the real power of technology may be as a tool to facilitate policy or behavior change rather than an end in itself.

Must an empathetic process produce an empathetic service? Human-centered design doesn’t always mean “be more human.” Sometimes, optimizing for the user just means something fast and intuitive—a two-click online solution rather than a phone call with a caring but chatty administrator, for example.

What are the limits of a protected innovation environment? Structured public innovation programs, like Agentes, often seek to create a protected space in which to incubate new ideas and approaches. At some point, however, any solution produced through such a process will have to be released into the wild and put to the test. We’re continuing to explore how innovators in the public sector can come to understand the necessary institutional prerequisites for (and the potential threats to) a product’s success, even while it is still being incubated.

Next week, the Agentes teams will present their projects at Condatos, the Latin America Open Data Conference, being held in Mexico City. We’re excited to see what they’ve been designing, and will report back more here. In the meantime, tell us what you think about the questions above.

We’re delighted to welcome Georgette Stewart and Emily Herrick to the team. As our accountant, Georgette is responsible for financial planning, budgeting, forecasting, internal controls, and compliance. Emily, who was our design intern this summer, continues with us as a part-time communications designer. Welcome to them both!

Earlier this summer, I received one of the more challenging design requests to arrive in my inbox: build a brand in rural Nigeria.

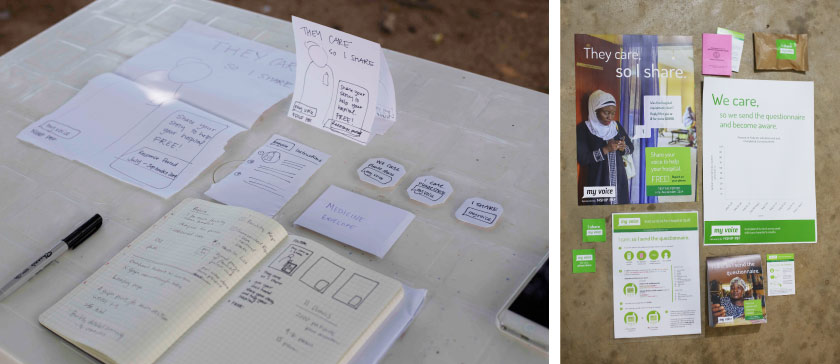

The assignment was in support of “My Voice”, an open source tool for citizens to provide feedback on select government programs that Reboot was developing in partnership with the World Bank. We were preparing to launch a pilot of My Voice in Wamba, Nigeria with a focus on collecting patient feedback from local healthcare clinics through an SMS-based survey. I was tasked with building the brand system to introduce—and encourage the use of—the My Voice tool in a new community.

Wamba is a rural county in the northeast corner of Nasarawa, a state right in the heart of Nigeria, and indicative of the many rural areas across Nigeria where healthcare service delivery occurs with very limited input from the patients themselves.

Here in New York, by contrast, I have many opportunities to comment on the quality of care that I receive. When I choose my doctor I use ZocDoc, a site similar to Yelp but focused entirely on healthcare. The site presents a long list of doctor options, which I can narrow down by specialty, distance from me, patient rating, and whether I want a male or female doctor. After reading the reviews left by other patients, I can make my final choice and visit their office for an appointment—vote with my feet, essentially. Following the appointment, I can enter my own feedback and review of the experience. A doctor or practice with too many negative reviews is not going to be seeing many more patients.

In Wamba, patients don’t choose their doctor. Typically, the doctor they see is in the nearest clinic they can access. That’s often the only option. When options don’t exist, the ability to shape your own experience doesn’t exist either. You can’t weigh options through others’ reviews, and you can’t vote with your feet. This situation challenges clinics too, which have to deal with whatever health issues come their way, regardless of available resources, staff, or proper equipment. Both sides of this service relationship want better outcomes, but have limited ability to realize them.

We built My Voice to help change this status quo, to provide patients with an opportunity to input on the quality of care that they receive and to provide clinics with more information about their patients’ needs. But just like ZocDoc—or any other crowd-sourced information platform—My Voice is only helpful if people are using it. The most intuitive, useful tool would ultimately prove useless if it failed to engage patients and health clinic staff.

This is where the need for brand building came in. We needed to build a visual identity to create awareness, define targeted messages to promote adoption, and ensure consistent communications to facilitate use. That much is clear in theory. Here’s how we did it in practice.

We knew from the outset that the visual identity system needed to be firmly rooted in the context of the culture to effectively resonate with those using the service. In Wamba, that meant a visual language that was easy to navigate and straight to the point since many prospective users would be illiterate. We focused on building a system that would be highly visual, easy to repeat, and easy to recognize. We wanted to realistically show what using the system looked like. Photographs, therefore, became key to the system, instead of iconography or illustration.

In the course of our research, we had taken plenty of photos that could have been visually appropriate. But they weren’t ethically appropriate since we hadn’t informed the individuals in those photos that their images would be used for anything beyond our own research. We keep a strict photo policy of informed consent and responsible use. We ensure that people know how and where their photos will be used, and that they are always asked permission before we take their picture.

So we needed new photos.

We revisited Wamba General Hospital and identified scenes that would be easily identifiable as clinics in Nigeria: periwinkle-colored curtains and a waiting room filled with wooden benches. We place our own team members into the scenes and took their pictures. We also got permission from clinic staff to use their photos in posters, flyers, and other materials for the My Voice system.

Having the right images is always important, but making sure we get them in the right way is much more so.

With the visual identity defined, next we needed to work on our messaging. Patients, health clinic managers, and health clinic staff all experience healthcare services differently, based on their unique roles in the system. Our messaging, therefore, needed to be tailored to demonstrate the benefits of My Voice with respect to each of their different experiences. Here’s where we landed:

Patients: “They care, so I share.” Patients wanted to know that their feedback was going to a trusted place, and that they could feel safe sharing. These messaging themes let patients know that by sharing their stories, they are helping their hospital to improve and better serve their needs.

Health Clinic Management: “I care, so I become aware.” The primary benefit to health clinic management is that the My Voice data provides insight into their hospital’s performance. This messaging theme tells them that by becoming aware of what their patients are experiencing (both positive and negative), they can be better informed about changes that will improve patient experiences.

Health Clinic Staff: “I care, so I send the questionnaire.” This was the toughest. We realized early on that the clinic staff were truly the “gatekeepers” to the process, since they have the task of informing patients about My Voice and registering them for the service. But if they view the program as a threat to their jobs, they’re certainly not going to use it. We addressed this by positioning them as an important role-player in the system. Their targeted message emphasizes expressing care towards patients, along with the importance of their position in the system, by giving patients the opportunity to share their stories.

Finally, we had to decide the most appropriate communications materials to ensure patients were aware of and knew how to use My Voice. For this, we looked to the context of the service. We asked ourselves: what did the environment and the design of the My Voice system offer in terms of touch points to design materials that would reach our target audience groups? Broadly, we developed three kinds of communications materials:

Promotional Materials. These include posters, table tent cards, and stickers. The posters are for clinic waiting room, treatment rooms, pharmacies, and offices. The table tent cards are for the clinics’ registration desks. One side faces the patients as they check in and out of the clinic. The other side faces the nurse or hospital staff registering them into the My Voice system. This interaction is an important one, making the registration desk a visible part of the system for both patients and staff. Lastly, the stickers are for placing on pharmacy bags as a reminder once patients leave the clinic. They are also given out at the registration desk as give-aways.

User Guides. These are for both patients and clinic staff to further aid in explaining the system. Patient user guides are folded into patients’ hand cards when they check out at the registration table. The patient hand card is a little pink booklet that tracks an individual’s medical history and important ID numbers. Since these documents are well-cared for, it ensures that the user guide would be kept close at hand and act as a visual reminder once patients leave the clinic.

Interactive Weekly Performance Posters. These posters help build awareness too, but more importantly close the feedback loop for patients inputting into the system. Here clinic staff fill in the survey data from the previous week. This demonstrates to both patients and clinic staff that their responses aren’t going into a black hole of bureaucracy.

Building the My Voice brand and all of its requisite components was a unique and exciting design challenge, to say the least. Often designers are tasked with changing behavior. In this case, the job was to create behavior in a very complex context. Since My Voice launched in mid-July, it’s been exciting to see that behavior begin to take root, but our work is far from complete. As the pilot period comes to a close in early September, we’ll be looking to feedback from patients, health clinic staff, and management to help us perfect both the My Voice tool and the brand we’ve built around it.